We speak with ELT course book author and teacher trainer extraordinaire John Hughes about critical thinking: what is it, how can teachers use it and what challenges it presents for teachers and students

At one end of the spectrum, language classes often include memorization and paraphrasing and at the other end, creativity in the form of writing and role plays. In the middle lurks critical thinking. What is its place in the language classroom?

Related Links

Who is John Hughes?

John's main course books titles are Life (National Geographic Learning) and Business Result (Oxford University Press). John's books have twice been nominated for ELTon awards and he has also received the David Riley Award for Innovation in Business English and ESP for the book ETpedia Business English. John is also a regularly contributor for the journals English Teaching Professional and Modern English Teacher and used to write a regular column for the Guardian Weekly’s ELT supplement.

John Hughes at IATEFL 2018

Image by TeroVesalainen

Transcript - Applying Critical Thinking in Classes and Materials Design (with John Hughes)

Tracy: Hi, everyone.

Ross Thorburn: This week on the podcast we have a special guest.

Tracy: John Hughes.

Ross: John Hughes is an award‑winning ELT coursebook writer and a teacher trainer. He's written over 30 coursebooks, as well as methodology books.

Tracy: He's twice been ELTon award finalist. In 2016, received the David Riley Award for Innovation in Business English and ESP for the book "ETpedia Business English."

Ross: Today we're going to talk to John about critical thinking. As usual, we've got three points. The first segment, we'll start off by asking John about what critical thinking is and why a language teacher should bother teaching it.

Tracy: Then we'll get some of his idea for critical thinking activities for different levels and age groups and finally...

Ross: We'll ask him about some of the challenges in including critical thinking in language classes and how we can overcome these.

What is critical thinking and why should language teachers teach it?

Ross: Hi, John. Thanks so much for coming on the podcast. Do you want to start off by telling us a little bit about what critical thinking is? I'm sure most of our listeners have heard of the term critical thinking before but it would be really useful to get your definition.

John Hughes: It depends on the context because the history of critical thinking is such that it's developed into different sorts of strands. We can talk about critical thinking in its very traditional sense which goes back to this idea of questioning. If you read texts about critical thinking, they start referring to people like Socrates.

In essence, it's about reading a text, questioning the evidence, looking more deeply at the sources and at the research. It's linked to this whole vocabulary that's emerged, things like post‑truths. It's this idea that everybody needs to be a critical thinker in terms of being able to look at information, news coming online and decide what is true and what is fake.

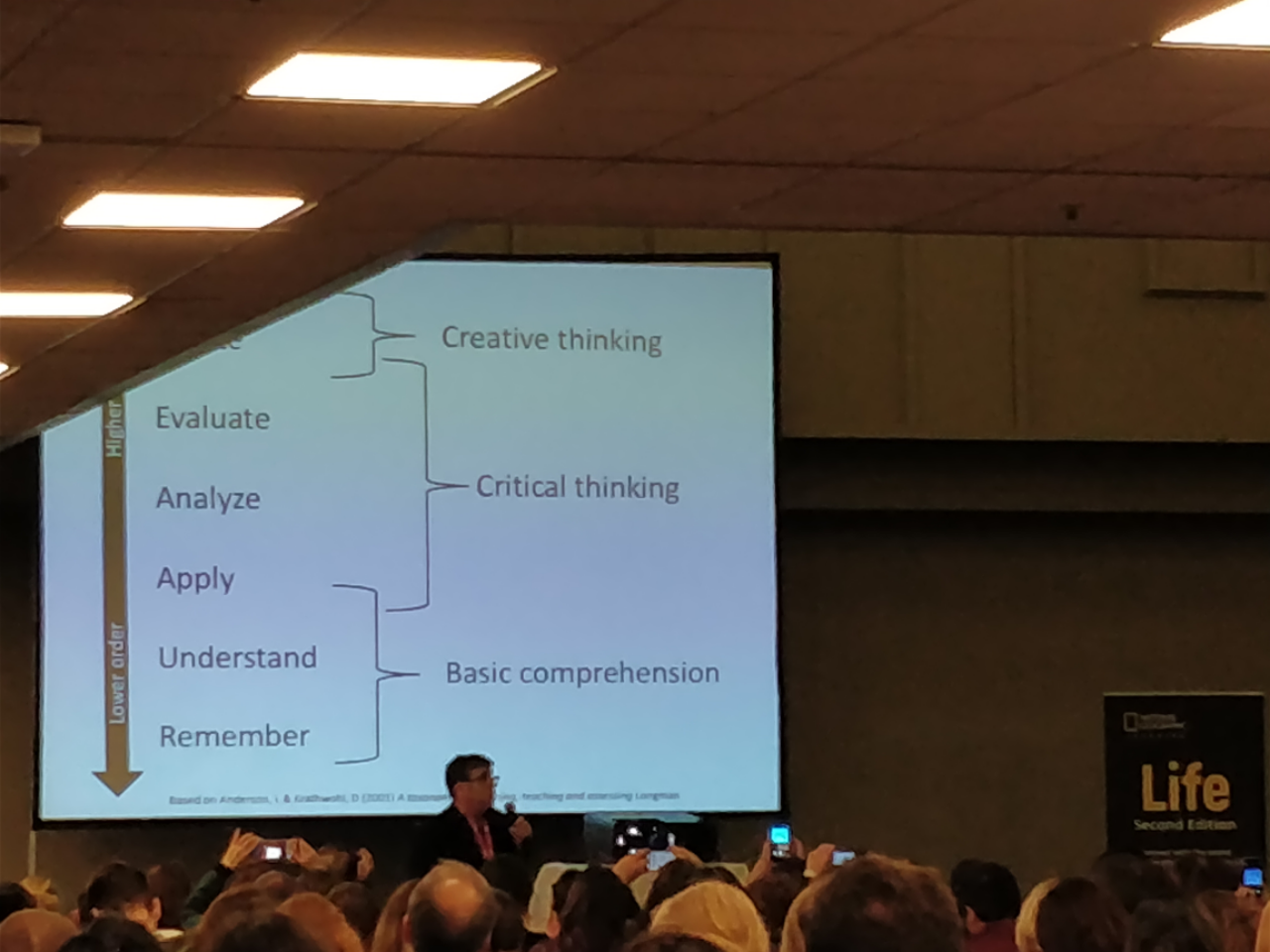

In terms of education and its impact on ELT, critical thinking is much more linked to the idea of lower order and higher order thinking. Language teaching is not just about memory and recall and basic understanding of language.

It's actually that ability to analyze language, to evaluate it, to go further with it, and perhaps to be creative with it. When you talk about critical thinking in that higher order thinking way, people start talking about Bloom's taxonomy.

Tracy: Given what you just said, John, why is critical thinking something that language teachers should bother to teach? Could we just argue that there is something that should be covered in perhaps other areas of education?

Ross: Like math class, or history, or science or something.

John: There's a couple issues here. In terms of English language teachers, if, in general, many of those use a communicative language approach, there's a lot of resources that already exist that encourage group communication, group problem solving, those types of collaborative tasks that by their very nature require students to apply some critical thinking.

We're well‑placed to develop those critical thinking skills anyway. The other side of it is whether as a language teacher we see ourselves more broadly. The term used is often the term educator. We're more than simply just teaching language.

We're also educating our students perhaps to approach things in different ways, think in different ways, that may influence their learning, not just within language learning, but also in all sorts of other areas, and their ability to what could be called life skills or communicative soft skills. It's that type of thing.

Ross: For teachers who are planning on using critical thinking activities in a lesson, what stage in the lesson do you think it would be most appropriate to add a critical thinking activity? Is there a particular stage, like in discovering language, or preparing students to talk, or as part of a role play, that you think it's most effective?

John: Yeah, it's a mindset in the sense of how you approach different parts of the lesson. For example, if you think about your lead‑in task, you might ask students questions to which they already know the answers.

For example, if you were doing a lesson on the topic of sports, you might say, "What sports do you like playing? Which sports do you like watching?" They would just draw on their existing knowledge.

If on the other hand, you showed students a photograph and it wasn't quite clear what they were looking at, or it was a slightly abstract photograph where the students had to think more deeply about what it was and what they thought the topic of the lesson might be about, you instantly get your tapping into students' more critical thinking.

If you're doing a grammar presentation, you might take the approach, "I'm just going to tell students the grammar rule. They're going to learn that rule." If it's learned that regular verbs end in ‑ed in the past simple, as a teacher you make a decision. Do I just tell them that that is the rule, or do I give them a task where they have to discover it?

Maybe they read the verbs in context in a text. They recognize that it's written about the past. You encourage them with a guided discovery approach to discover the rule. I would say that's a balance. It's all about using both approaches to teaching a grammar point.

Ross: Is it like a lens through which you can view a lesson and ensure it's balanced, as in the same way, you might look at your lesson plan and say, "Is there enough movement in there, or is there enough variety in interaction patterns?" Is that how you see it?

John: Yeah, I think you can look at when, for example, as a coursebook writer, if I write a lesson, you're looking at the flow of your tasks and you're aware that sometimes you're writing exercises which could be called lower order thinking.

You might think, "Well, I've done four or five of those in a row. It's time that I stretch the student more. I'm going to include some higher order thinking task." Equally, don't always make your lessons all singing or dancing creative experiences. Sometimes students just need to do those more traditional language exercises.

Critical thinking activities for ESL classes

Tracy: Can you introduce some examples of typical critical thinking activities that teachers could use in their classrooms?

John: Simple approaches would be when you do group work, and you ask students to brainstorm all the different types of holidays that might be appropriate for a certain person. Afterwards, look at what you've brainstormed, choose the two or three best ideas. Then choose the best one and present it to the class.

What you've got going on there is some creative thinking with the brainstorm. The critical thinking kicks in because you actually start to analyze and evaluate those ideas. It's that kind of process.

Teachers can use that approach all the time with all lessons, particularly case studies, problem‑solving tasks, that kind of thing. That all requires students to read deeply, think deeply about a problem and respond in a reasoned, rational kind of way. It's useful for practicing the English they want. It's also a skill that they use or need to develop their own work.

Ross: I guess up to this point we've been talking about using critical thinking with adults or older students. Do you think critical thinking naturally lends itself more to adults than to teaching teens or teaching young learners perhaps?

John: I don't have much of a background in teaching young learners, but people who do...For example, a colleague of mine called Vanessa Reis Esteves, she wrote a book called "ETpedia Young Learners."

She would probably argue that the six, seven‑year‑olds at that age there's a natural critical thinking mindset. There's that age when kids ask "Why?" about everything and question everything.

In terms of maybe teenagers, if we imagine that they're quite a visual generation, critical thinking tasks with images are quite a nice way into a lesson. For example, there's a very good book called "The Mind's Eye." I think it was edited by Alan Maley. It was one of the first books that just included sets of pictures.

Instead of asking students to describe what was in the picture, they had tasks like, "Imagine you just walked into this picture. What would you say?" or "Look at this picture. What do you think was happening before this picture?" or "What's the character in the picture about to say to the other person?"

Also the use of video, simple tasks like playing a stretch of video with the sound off and get students to script that and so on. It's quite a simple way to get students personalizing text or using text in quite creative ways.

When should we teach critical thinking in EFL, and when should we not?

Tracy: Do you think there are cultures or contexts in particular which critical thinking tasks work better than others?

John: Yeah, it's a contentious area. I've read all sorts of research papers on this topic and looking at critical thinking and whether it's cultural. I'm a bit skeptical of it all because I've met lots of individual students who have come to class naturally with a critical thinking mindset. They've been from all over, from all sorts of different parts of the world.

There's an educational culture. There's obviously the education system that you've grown up in, and have you been in classrooms where you've been encouraged to ask questions, or not accept everything at face value. That naturally impacts on, when you arrive as a student in class, what your natural assumptions are about what happens in the classroom.

If you've got a student who's come through an education system where they've been encouraged to put up their hand and ask questions themselves, naturally that student comes across as being more of a critical thinker. We also shouldn't confuse the fact sometimes that students not saying anything does not equal them not thinking critically about something.

Ross: I'm sure most teachers have been in the situation before of giving students a discussion or debate and it ends up finishing a lot quicker, maybe without the depth that we were hoping for. What can teachers do to make sure that those critical tasks work more effectively?

John: Maybe the problem is that we haven't actually spent the time providing them with the language they need to express their opinion. There's two things going on here. There's, perhaps, students are thinking critically, but they don't have the language they need to express themselves, to say what they're thinking. We have to make sure we've taught them the language they're going to need.

Tracy: John, you just mentioned that preparing students linguistically for our critical thinking task. What might that process actually look like? What would a typical preparation for a critical thinking task be?

John: You have to scaffold things. Sometimes if you want students to have a certain discussion or write a particular text, I do think it's helpful to have given them some models. They may have listened to a conversation that models certain language and certain ideas, or they might have read a text.

They need time to have studied those things and identified their internal structure or the key phrases that might be useful for themselves. Planning time, students notoriously don't spend much time planning.

If you ask them to write an essay, you've have that experience of students starting to write the essay straight away without spending a useful 5 or 10 minutes just brainstorming, planning, thinking about the structure. It's that planning critical thinking time that's the difference between a really good essay and one that meanders and loses its way halfway through.

More about John Hughes

Ross: Finally, for anyone who wants to read more about critical thinking, your blog is www.elteachertrainer.com?

John: That's right.

Ross: Do you have anywhere else that you'd recommend for listeners to go to read more of your stuff or to find out more about critical thinking?

John: Well, we're bringing out a methodology book with National Geographic Learning. It'll be out the beginning of next year, which gives the background theory but also will include practical ideas and activities. Really just demonstrate how critical thinking can be integrated as part of language teaching.

The other course book series, I have a series called "Life" with National Geographic Learning which was our attempt with a general English course to highlight and feature the idea of critical thinking and creative thinking into language teaching so that the material we've provided hopefully provides a balance between lower order and higher order thinking.

Ross: Thanks again so much for coming on the podcast, John, and sharing all those amazing ideas.

John: You're welcome. It was very nice to speak with you. Thanks.

Tracy: Bye.

Ross: Bye.